‘Godard par Godard’ Review: He Was as Fascinating as His Films

One of the grand paradoxes of Jean-Luc Godard is that he was a radical, an outlier, a filmmaker who guarded his purity and always looked askance at “the system,” yet because the nature of filmmaking is that it requires a lot of money, and is connected to fame, and produces images that can spread with iconic power, Godard was an outsider who was also an insider; a poet of cinema who made himself a celebrity; an artist who bridged the larger-than-life, old-school ethos of movies with the forbidding imperatives of the avant-garde.

All of that contradiction is on full display, with a luscious kind of resonance, in “Godard par Godard,” an hour-long documentary, written by Frédéric Bonnaud and directed by Florence Platarets, that was presented at the Cannes Film Festival today as a tribute to Godard, eight months after his death on September 13, 2022. The documentary was shown along with Godard’s final film, the 20-minute-long “Trailer of the Film That Will Never Exist: ‘Phony Wars’.” All of which sounds like one of those Cannes–only special events, but au contraire: This is a program that was meant to be seen by the world at large, and with any luck it will be distributed that way. It’s an homage that invites us to look back, with fond fascination, on all the cinema Godard gave us, and on who he really was.

In 1960, when he released “Breathless,” the spryly insurgent postmodern gangster movie that François Truffaut, in one of the documentary’s many choice clips, hails as the greatest first film ever made (along with “Citizen Kane”), Godard was catapulted onto the brightly lit pop-culture marquee of the new movie revolution. And he himself would become as much a part of that as his movies.

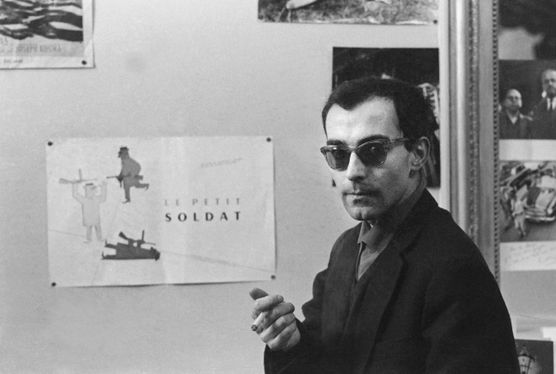

Godard, who early on flirted with being an actor, knew how to play the role of himself. For years he gave hundreds of interviews, seated in front of the camera like the handsome scowling art star he was. “Godard par Godard” draws together an extraordinary array of archival footage that even most Godard fans have probably never seen: on-the-set looks at Godard shooting his ’60s classics, a director at once casual and meticulous, or scenes of him wandering through the streets and cafés of Paris with a cigarette in hand, plus a cornucopia of television interviews in which he presents himself in that debonair austere way — the dark glasses he never took off, the delicate handsomeness set off by that cleft chin, the unmistakable voice (so calm yet with a hint of a tremble in it, a nagging rumble of passion), the natty jackets, and the impish smile that began to close down around 1966, when he was getting more extreme in his fervid conceptual Marxist I-must-destroy-cinema-in-order-to-save-it absolutism, and he began to look dour and a little desperate, like an outlaw on the run.

There’s great footage from the Cannes Film Festival in 1968, when Truffaut and Godard, shouting down reporters as the two commanded the spotlight, insisted that the festival itself must be shut down in solidarity with the French workers and students who had banded together to create the mythic moment known — and romanticized by bourgeois stalwarts everywhere — as May ’68. May ’68 was a workers’ uprising, but it was also a social pantomime of uprising that was all about itself. It transformed — and in certain ways damaged — Godard by convincing him he was at the forefront of a much more radical shake-up of cinema and society than he was.

“Godard par Godard” is structured around a chronological presentation of Godard’s films. There are no talking-head interviews, except for what we see in the old black-and-white clips — or, decades later, Godard on “The Dick Cavett Show.” But in the case of each film, from “Breathless” to “A Woman Is a Woman,” from “Contempt” to “La Chinoise,” from “Tout va Bien” to “Numéro Deux” to “First Name: Carmen” to “JLG/JLG — Self-Portrait in December,” the movie creates a vivid image of where Godard was at when he made each movie. The achievement of Florence Platarets is that she elevates a snapshot filmography into a spiritual biography.

The film spills over with fresh details. We all know about “Breathless” and the jump cut, but “Godard par Godard” gives you a sense of how the movie was improvised, and how Godard used every technique — wide-angle closeups, hand-held tracking shots — that you weren’t supposed to. Overnight, he replaced the strictures of cinema with something free.

But Godard had his own strictures. There’s an interview with Anna Karina, when they were married partners in art and life, in which she talks about how she couldn’t change a word of Jean-Luc’s scripts, though she says he worked with his actors so closely that they become vibrant collaborators. There’s an amazing sequence in which we see the dance scene from “Band of Outsiders” as it was being filmed…in a café full of civilians! Godard talks about how the Brigitte Bardot nude scenes in “Contempt” were done to satisfy the film’s American distributor (but Godard turned exploitation into art), and he describes how his whole impulse was to fuse documentary with fiction. We see him interviewed on the beach at Cannes, talking about how much he hates zoom shots.

There’s a point in the ’60s when Godard started doing what Dylan did: using the dumb questions of the press to turn his answers into performance art. He was saying, “You’re all part of the system. I’m not.” And he wasn’t; he’d left the system behind. But the system also left him behind. As he grows into middle age, you can see him pass through the five stages of alienation, until he comes out the other side. Appearing on the Cavett show to promote his comeback, with the 1980 film entitled “Slow Motion” (released in the United States as “Every Man for Himself”), he’s actually quite ebullient. He rejects the idea that he ever went away, but says that he’s done with anguish, and also that the new movie, his “second first film,” is the first one in which he’s expressing who he really is.

I think he’s fooling himself (his ’60s films were just as personal), but his new lease on life is infectious, and it fueled the rest of his career. “Godard par Godard” follows the filmmaker into the 2000s, when he’d sealed himself into his Swiss bunker and his work grew trickier than ever. Yet he seemed content living off the grid of movie fame, smoking his cigars and preaching to a diminished choir.

Speaking of which, “Trailer of the Film That Will Never Exist: ‘Phony Wars’” would be a minor curio if it weren’t positioned as the last testament of Jean-Luc Godard. It’s unlike anything he’s made before: a series of collage photographs, many with printed aphorisms, each collage mounted on a piece of white Canon pasteboard. You could call the film a brainy version of The Complete Godard. Here is “our war,” here is May ’68, here are pensées like “But the bottom line is that there are no grownups,” here is his plan for a film about revolution built around the writings of a Leon Trotsky acolyte-turned-heretic. And here’s Godard ending the film by describing something being “rented to what wasn’t yet the Jewish Agency.” Yes, those are the very last words of Jean-Luc Godard’s career. Make of them what you will.

Personally, I’ve never known what to make of Godard. To me he’s a mystery, a muse, a symbol of what made me want to merge with movies, an artist so baffling he often left me infuriated, and an artist so powerful that he forged the very soul of modern cinema. What did it all mean? Godard only knows.