‘Let the Canary Sing’ Review: Captures Cyndi Lauper’s Cracked Pop Joy

When you see a documentary about a game-changing pop star, you assume you’re going to get the story of the music, and also a good look at the life, and that there’ll be enough (on both counts) to go around. I was eager to see “Let the Canary Sing,” a documentary portrait of Cyndi Lauper, because it’s directed by Alison Ellwood, who made “The Go-Go’s” a few years back, and that movie had everything: the drama, the trauma, the saga of a total pop-music reset, as we watched the Go-Go’s bust down doors that had been too tightly shut for too long. Cyndi Lauper was no less revolutionary a figure, arriving in the early ’80s, along with Madonna, to announce that we were in the midst of a seismic new definition of what it meant to be a female pop star. The definition was: a star who could rule — and change — the world.

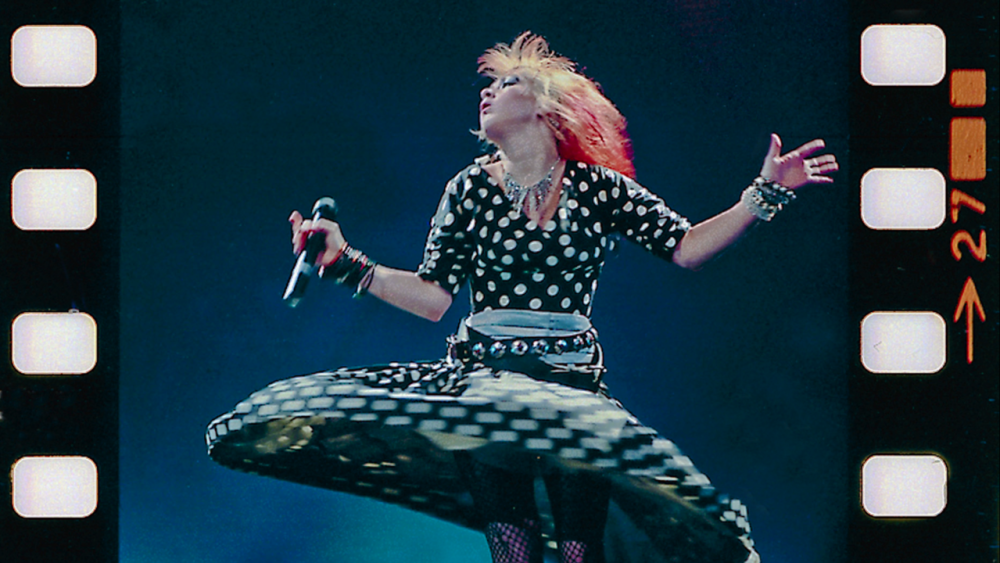

When she first launched into orbit in 1983, Cyndi Lauper was such a powerful singer, so brazenly anthemic in her joy and attack, with such a head-turning new image (the punk cockatoo hair, the frosted kewpie-doll-meets-Sid Vicious lip pucker, the stylized Brooklyn street-urchin voice, the thrift-shop layers of dresses and earrings and bangles and fishnets, and the way that she’d contort her body, as if she were in too much ecstasy to worry about which direction her limbs were pointing) that she seemed at once totally outside the box and utterly inevitable. When you disrupt and define the pop landscape as thoroughly as Lauper did, there’s going to a be a certain drama to the story of how your music and your creative life force came into focus, and “Let the Canary Sing” does an excellent job of tracing how Cyndi Lauper came to be…Cyndi Lauper.

Yet it’s sort of an idiosyncratic movie, because that’s all it does. I can’t say, for sure, what “larger story” I was looking for. The film sketches in aspects of Lauper’s biography, like the romantic relationship she had with David Wolff, who was her manager through the glory days, as well as her ardent LGBTQ activism, starting with her presentation of “True Colors,” in 1986, as an anthem for the gay community when it was being ravaged by AIDS.

That said, the portrait of Lauper that emerges from “Let the Canary Sing” doesn’t just feel meticulously laudatory and controlled; it feels oddly minimal. In recent years, there have been a number of streaming documentaries about pop stars, like “Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry,” “Pink: All I Know So Far,” “Gaga: Five Foot Two,” and “Jagged” (about Alanis Morissette), that were certainly controlled and protective, to the point that some critics (though not me) accused them of being hagiographic. But within the school of documentary-as-image-polishing, they revealed a great deal about who these stars are as human beings. “Let the Canary Sing” is satisfying when it focuses on Lauper’s music and her ragamuffin-street-kook persona, but you feel like you’re getting the super-bite-size version of Cyndi Lauper’s life.

For its first 50 minutes or so, the film is terrific. Lauper, born into a boisterous Sicilian family in 1953, was 30 years old by the time she made it big, yet she knew from a young age that she wanted to be a singer. The movie traces the more than 10 years she spent working away at it. In her family’s cold-water flat in Brooklyn, she grew up watching “Queen for a Day” on TV and also the Beatles, who we see priceless footage of her and her sister, Ellen, impersonating. Catching Patsy Cline on “The Arthur Godfrey Show” was big for her. But by the time her family moved to Queens, her parents were divorced and she had an abusive stepfather. She left home at 17, going to live with Ellen, who was gay and open about her sexuality. Cyndi herself was a wild weed, and in that atmosphere of tolerance she began to bloom.

At first, Lauper played in cover bands. We hear a live recording from the period when she was imitating Janis Joplin (startlingly well), which at one point blew out her vocal cords. It was in 1980 that she joined the band Blue Angel as lead singer, and we start to hear the blasting operatic power of her voice. I confess that I never knew this part of the story, and it’s a revelation. Blue Angel sounded like they wanted to be Blondie, and they had a few songs, like the single “I’m Going to Be Strong,” that really kicked. Lauper’s presence onstage, from the clips we see, was volcanic, but success bypassed the band. (They’d come along a little too late to be new wave, a little too early to be post-new wave.) People kept telling Cyndi that she should go solo, and after Wolff became her manager, it happened. But she was sued by her previous manager and had to go to court (and go bankrupt) to be free of him. At the end of the trial, the judge said, “Let the canary sing.”

Who, as a singer, was the canary going to be? Wolff hooked Lauper up with Epic Records executive Lennie Petze, who put her together with the producer Rick Chertoff. It turned out to be an ideal match, but first they had to confront a giant bump in the road that, in hindsight, defined Lauper’s independence, her artistic intuition, and her primal feminism. Chertoff had found a song he thought it would be perfect for her to sing: “Girls Just Want to Have Fun,” written and recorded by the Philly rocker Robert Hazard in 1979. We hear his version, and it’s a weirdly disposable piece of punk bubble gum that sounds like the worst song ever recorded by the Tubes. It was also a song about girls as gazed at by dudes.

Lauper heard it and said to Chertoff, “I will never do that fucking song.” But Chertoff got her to do it by completely revamping the song, along with her, a project they worked on together for months, starting with the exultant opening that evoked an organ playing at a summer carnival. The lyrics changed; the rhythm changed; the chords and the melody went from being quick and choppy to deeply madly infectious. And Lauper’s singing made it momentous. The song, as multi-layered as it was catchy, was saying: Girls just want to have fun because…well, who doesn’t want to have fun? But it was also saying, in its dancing-in-the-streets way: Girls just want to have fun exactly the way that guys just want to have fun. Fun meant fun, it meant freedom, and it meant the exuberance of self-invention. The song was a cheeky triumphant answer to 80 years of “What do women want?” clueless male head-scratching.

You might think it was destined to be a hit, but it wasn’t — at least, not out of the gate. The prospect of putting out the follow-up single, “Time After Time,” soon afterward was floated, but Lauper recalls the incisive rationale with which she fought that idea. The Motels, she said, had been a great band who had led with a slow single; they never recovered from that. What ignited “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” was that Cyndi, picking up on the camp aspects of the song’s video (in which the wrestler Captain Lou Albano portrayed her “daddy dear” who’s “still number one”), inserted herself into the world of pro wrestling, using her Gracie Allen-meets-Betty Boop put-on personality to become part of that cartoon universe. It worked. It made her seem mainstream, and at that point the single took off.

There are terrific stories and clips in “Let the Canary Sing.” The film takes us inside the songwriting process, and we see how Cyndi, collaborating with Annie Liebovitz, turned the cover shoot for “She’s So Unusual” into an act of imaginative projection. The most stunning sequence in the film is a clip, from 1985, in which Lauper and Patti Labelle do a duet of “Time After Time.” Vocally, the two keep circling each other, as if they’re in a delirious slow-winding gospel duel, and the whole performance is heightened by Billy Porter, who narrates what’s going on as if it were a sports event.

Cyndi Lauper had a rather dramatic fall-off as a pop star. “She’s So Unusual,” with its cascade of singles, placed her on that magical ’80s Olympus along with Madonna and Michael Jackson. And though her second album, “True Colors,” couldn’t match it, it had the sublime title track. But her next two albums, released in 1989 and 1993, were relative duds (though the first of them generated a modest hit, “I Drove All Night”). Whatever it was in Lauper’s voice that had so majestically connected in 1983 could no longer seem to find a hook worthy of it.

The documentary shows you that she did have a second life as an artist, coming back by writing the songs for the Broadway musical “Kinky Boots” (and winning a Tony for best original score, the first woman to win solo in that category). In 2010, her “Memphis Blues” album was a niche triumph, and she remains all over the cultural map. Having already done a bad movie (“Vibes”), she did “Celebrity Apprentice,” she did ads for the psoriasis drug Cosentyx, and she continued to tour. And the film pays tribute to the singular passion of her activism. But once she leaves the arena of larger-than-life pop, “Let the Canary Sing” becomes rather rote as a documentary. And that’s because it hasn’t found enough of a story behind the litany of Lauper’s achievements. It shows you why she was so unusual, and so great, without ever quite convincing you that you’re seeing all her true colors.