‘The Killer’ Review: David Fincher’s Hitman Film Is All Methodology

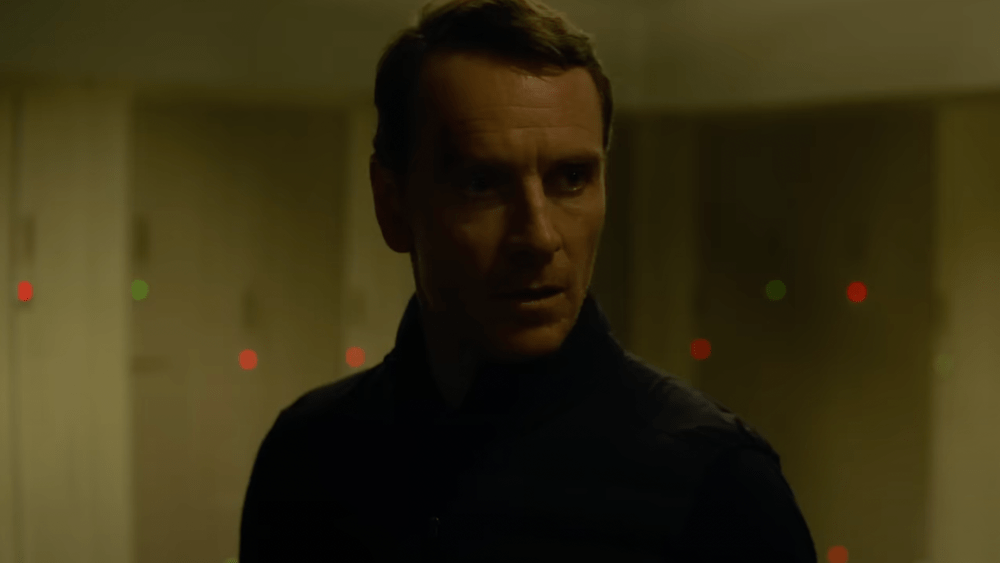

In the bravura opening sequence of David Fincher’s “The Killer,” we watch the title character, a cold-as-dry-ice professional hitman who is never named, as he prepares to assassinate his latest victim. The hit is taking place in Paris, and the target is some sort of powerful corporate tycoon who we, like the killer, know nothing about. His home occupies the entire penthouse floor of one of those ornate block-long Parisian apartment buildings. The killer, who is played by Michael Fassbender, has set up his sniper’s nest in an empty, darkened WeWork space across the street.

He’s got his huge black telephoto rifle, placed on a table whose height he can manipulate. The gun shoots large gold bullets that can penetrate glass without shifting their trajectory. The killer has nothing to do but wait for the target to arrive, and during that time, he speaks to us on the soundtrack, talking about his methodology, his philosophy, and the fact that if you don’t like waiting around, this work is probably not for you.

“The Killer” turns out to be a movie about waiting around to kill people. Fassbender speaks in a low affectless drone, saying things like “On Annie Oakley jobs, distance is the only advantage” or “No one who can afford me needs to waste time winning me over to some cause” or “Most people refuse to believe that the great beyond is anything more than a cold, infinite void.” He sounds as dread-squeezed and controlled as Martin Sheen in “Apocalypse Now” when he said, “Never get out of the boat. Absolutely goddamn right.” Committing a hit may be mostly about counting down the minutes and hours, but Fincher builds the sequence with a veteran suspense filmmaker’s cunning.

Just watching Fassbender do push-ups in his black rubber gloves wires up the atmosphere. At one point, the door of the WeWork office opens. And when the killer puts music on his earbuds (the Smiths’ “Well I Wonder”) to get into his groove, it becomes the needle drop as homicidal pop-opera soundtrack. The target arrives, and as we watch him move about the apartment, the film generates the hypnotic tension one remembers from “The Day of the Jackal” or certain moments in Brian De Palma films. We realize that the chemistry of cinema hasn’t just put us in the killer’s shoes — it has put us on his side. We want to see him do the deed.

The posters and ads for “The Killer,” a Netflix movie that’s premiering at the Venice Film festival, feature a terrific tagline: “Execution is everything.” The pun is crystal clear in its cleverness, yet there’s a third layer of meaning to it. For just as the killer’s execution of his job depends on coldly calibrating every moment (no empathy, no mistakes), Fincher has made “The Killer” with more or less the same attitude. The film is based on a French graphic novel, written by Alexis “Matz” Nolent and illustrated by Luc Jacamon, that was published in 12 volumes starting in 1998. And as staged by Fincher, from a meticulous bare-bones script by Andrew Kevin Walker (who wrote Fincher’s “Se7en”), the film is all about its own execution. It’s a minimalist nihilist action opera of procedure.

In that opening sequence, it works brilliantly, never more so than when the control-freak precision suddenly falls apart. For the killing does not go as planned. The target has a visitor, a statuesque woman done up in designer S&M regalia, and let’s just say that her presence gets in the way. When the hit fails to come off, it’s a major mess-up, and Fassbender, toting his lethal equipment and hopping on a motorbike, is as diligent and detail-oriented escaping from the crime scene as he was in setting it up.

But his cool façade starts to melt away after he takes a plane to the Dominican Republic, where he has a large house, which has been invaded. He rushes to the hospital, where his live-in partner (Sophie Charlotte) is laying in bed on a respirator. She has been attacked by goons who were hunting for Fassbender. As we learn, she told them nothing. But these are the stakes: You don’t screw up a hit like the one in the opening sequence without consequences. The forces of execution are now after him.

I don’t want to give away much more of “The Killer,” because the movie is all about discovering Fassbender’s journey of vengeance and self-defense right along with him. But I will say this: As carefully made and, at moments, ingenious as it is, the film never matches that opening sequence for sheer screw-tightening excitement. What the Fassbender character goes on to do, while it certainly holds our attention, starts to seem more and more like heightened but conventional variations on the actions of a whole lot of characters we’ve seen in a lot of other thrillers.

Fassbender learns that there were two executioners who came after him at his Dominican Republic home, and he’s got to confront both of him. He also has to find out who the original client was, and he does that, in one of the film’s more gripping sequences, by dressing as a delivery man with an oversize plastic waste bin and sneaking into the office of Hodges (Charles Parnell), the lawyer who recruited him into this business.

The driving idea of “The Killer” is that Fassbender’s hit man, with his cool finesse, his six storage spaces filled with things like weapons and license plates, his professional punctiliousness combined with a serial killer’s attitude (the opening-credits montage of the various methods of killing he employs almost feels like it could be the creepy fanfare to “Se7en 2”), has tried to make himself into a human murder machine, someone who turns homicide into a system, who has squashed any tremor of feeling in himself. Yet the reason he has to work so hard to do this is that, beneath it all, he does have feelings. That’s what lends his actions their moody existential thrust. At least that’s the idea.

But watching the heroes of thrillers act with brutal efficiency (and a total lack of empathy for their victims) is not exactly novel. It’s there in every Jason Statham movie, in the Bond films, you name it. “The Killer” is trying to be something different, something more “real,” as if Fassbender were playing not just another genre character but an actual hitman. That’s why he has to use a pulse monitor to make sure his heartbeat is down to 72 before he pulls the trigger. It’s why he’s hooked on the Smiths, with their languid romantic anti-romanticism — though as catchy a motif as that is, you may start to think: If he’s such a real person, doesn’t he ever listen to music that’s not the Smiths? In “The Killer,” David Fincher is hooked on his own obsession with technique, his mystique of filmmaking-as-virtuoso-procedure. It’s not that he’s anything less than great at it, but he may think there’s more shading, more revelation in how he has staged “The Killer” than there actually is.

Fassbender, with his morose anonymity, is the perfect actor to inhabit this role, his sullen snake-like glare emitting silent notes of rage and fear. Yet it’s not like we ever feel close to this dude. And there’s one key episode that, for me, didn’t parse at all. Fassbender faces off against another killer, played by Tilda Swinton, and whatever excitement one feels at the casting is undermined by the decision to have Swinton play the character as a kind of abashed and typical British gentlewoman. Why does Fassbender get to go all cold-crazy-socio while Swinton doesn’t have the chance to create her own fatal stone freak? It feels like a lost opportunity, a stacked deck, and a case of a movie devoted to procedure suddenly winging its own rules.